In the last year of my undergraduate degree, I did two quarters 1 of undergraduate research, and the purpose of this post is to capture some of the research processes and techniques I pieced together during that time.

One thing that surprised me about research was the sheer amount and breadth of material one winds up reading, and how often you end up needing piecemeal bits from many different sources. For example, some of the topics I studied had books with multiple chapters dedicated to it, whereas others were covered in a single section or even just a paragraph here and there. For my level of mathematical maturity, most of the things I needed could be found in textbooks and occasionally papers and journal articles, but it was sometimes the case that extended treatments could only be found “off the beaten path” in lecture notes, expository writings, or theses/dissertations.

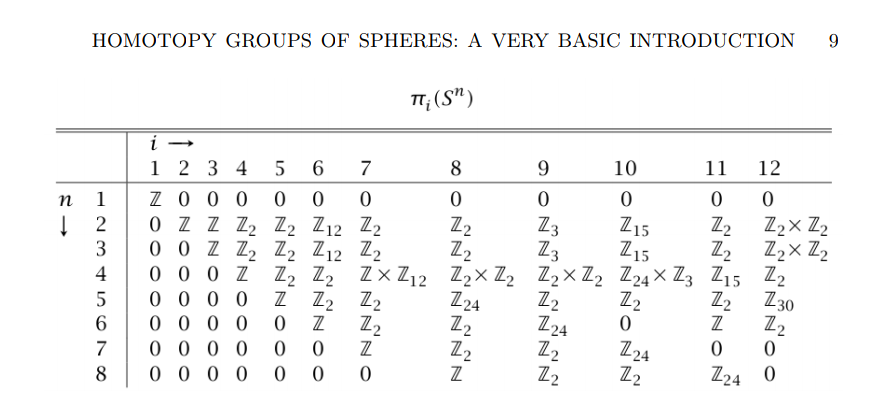

It was also surprising how difficult it can be to rediscover any particular result. An early example of this for me occurred when I began trying to sort out what was known about the higher homotopy groups of spheres.2 3

I began by churning through many sources resulting from standard keyword searches, not really knowing which results were significant or not. At some point, I found a paper that had tabulated the order of many torsion subgroups, and it was not until many weeks later that I realized that this was a useful thing to have because it included groups in the “unstable” range.4 Going back and finding that specific document, however, wound up taking much longer than I’d expected.

As a result, I decided that I needed to set up some kind of system for how I read and parse papers, textbooks, and other random documents, with the express purpose of making this kind of “backtracking” slightly less onerous.

Within Mathematics, we are lucky that both LaTeX and the arXiv are the norm, and thus most research in our field ends up in open access PDFs. The problem then becomes managing a large number of documents, plus personal notes or annotations associated with each one, and being able to find these easily later. This is made difficult by the fact that many people use awful naming conventions for their documents, and also that some documents lack the OCR layers necessary to search within them for text.

I thus sought to build some kind of process for how I read, parse, and recollect information, and came up with the following guidelines/constraints:

- Documents need to be roughly separated, based on which of these categories they fall into:

- Textbooks

- Published and peer-reviewed papers (e.g. from the arXiv)

- Expository notes, lecture notes, and other miscellaneous “unofficial” writing

- All PDFs should be searchable in some fashion

- Documents should be imported into some kind of reference management software that handles populating metadata, renaming and sorting files, and maintaining a global BibTex file.

- There should only ever be one canonical file for each reference, .e.g. a single PDF file

- Everything needs to sync between my devices (computers and Android phones/tablets) so I can read and annotate the same document everywhere

- Everything needs to be read in something that supports adding notes, annotations, and bookmarks.

- Any annotations and notes put into documents need to be easily searchable, ideally providing a quick way to jump directly back to the right spot in the right PDF

Although it required cobbling together several different tools, I’ve managed to land on a process that roughly meets these criteria, so I’ll try to lay out an outline of what I settled on.

Separating Documents

The first step is controlling what is downloaded -– although this requires manually downloading anything you want to keep, you can at least be assured that everything that does end up on your computer is intentional.

This is useful because not everything I read ends up being relevant -– perhaps I open a PDF to skim it based on a keyword search on the arXiv, which ends up being too far afield to be useful to my particular research project. In such a case, I would not want such a document mixed in with ones that I’d consider potentially useful, as it just adds noise.

Fortunately, this is handled pretty well these days by Chrome’s built-in PDF viewer. I can simply skim papers in the browser, and then manually download anything that looks promising. Since every PDF file is now an intentional download, I simply drop them into one of several subfolders as soon as they are downloaded.

Separation by type is important for me because I prefer to use Calibre to manage textbooks, while I prefer to store papers and lecture notes separately in Zotero. Calibre excels at populating metadata and cover images for things like textbooks, while Zotero has nicer organizational capabilities and is particularly good extracting citation information from papers and even expository documents on occasion.

As such, I have one Books folder that I set up Calibre to watch, and a second Papers folder for items intended for Zotero.

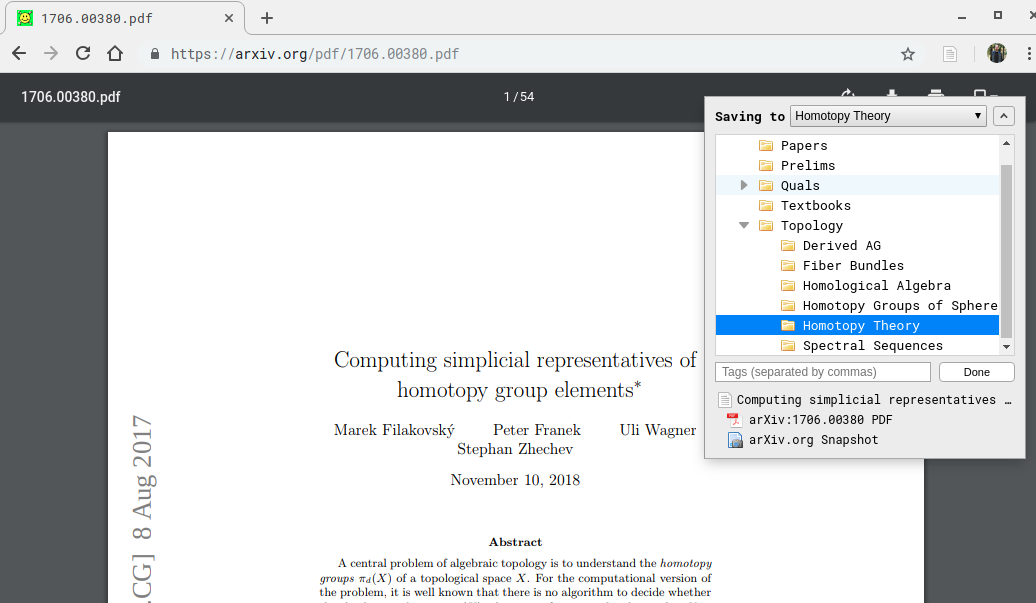

With Zotero, there is also a browser extension for Chrome which lights up any time you are reading a PDF document. When clicked, it can send the page directly to a collection of your choice, where it will create a bibliography entry for it and automatically download the PDF:

This is especially nice because it allows you to organize and tag things on the fly, and skip the entire process of downloading into the Papers folder and importing later.

Adding OCR Layers

Occasionally, Zotero will have issues finding citation information for a document. From what I understand, this is because its algorithm relies on reading a random sample of OCR’d text within the document and searching the internet for exact text matches. If the PDF does not contain an OCR layer, then this text can’t be extracted, and incidentally, the PDF will also not be searchable.

There are many ways to go adjoining OCR data to a document, but I’ve settled on the wonderful OCRmyPDF tool. Usage from the command line is extremely simple, generally something along the lines of ocrmypdf infile.pdf outfile.pdf.

Many other OCR solutions miss many of critical features that this tool gets right -– for example, it positions the OCR’d text accurately, which is important when it comes to highlighting and extracting annotations correctly down the line. It also maintains the original PDF resolution, whereas other tools tend to degrade the quality.

But most importantly, it tends to just work on everything thrown at it, and the default settings tend to produce excellent results.

It also lends itself nicely to scripting and automation. There are scripting approaches described in their documentation; two excellent options include setting up a cron job that runs over your entire “Downloads” directory periodically, or setting this folder up as a “hot” watched folder to OCR each new PDF as it comes in. Since OCRing is a computationally intensive process and I primarily use a laptop, I opt to just manually run this on individual PDFs when I find out that OCR layers are missing.

Importing Into Management Software

As mentioned above, my two primary document managers are Calibre and Zotero. I choose these because there’s no real lock-in; I’m able to store my libraries in plain directory structures, so these primarily help sort, organize, search, and enrich the metadata of what I already have. If both stopped working tomorrow, I would have no issues continuing to use my library directly from the file system.

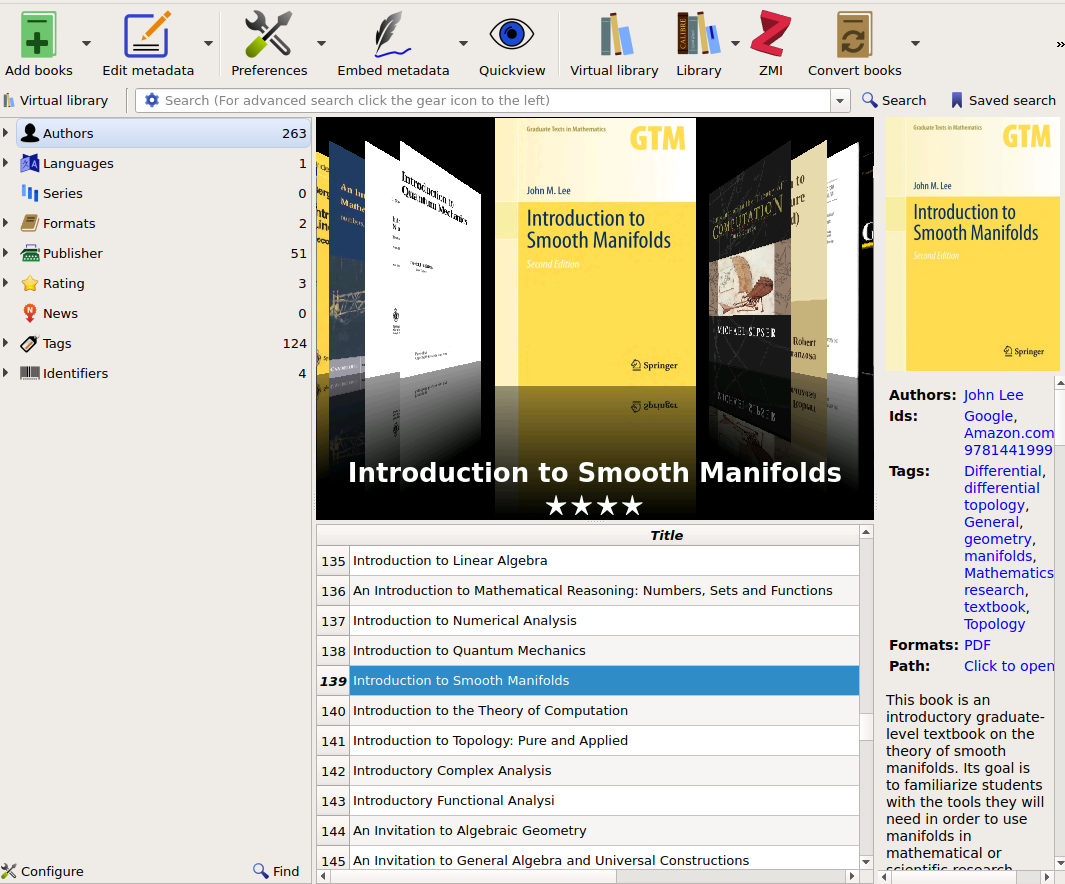

I tend to use Calibre for more general reading, primarily because it handles directory organization, file naming, and downloading covers for books. This makes for a nice and clean display in casual reading applications:

Since it has a “Watch Folder” feature, it is a relatively simple matter to set it to watch the Books folder for new downloads.

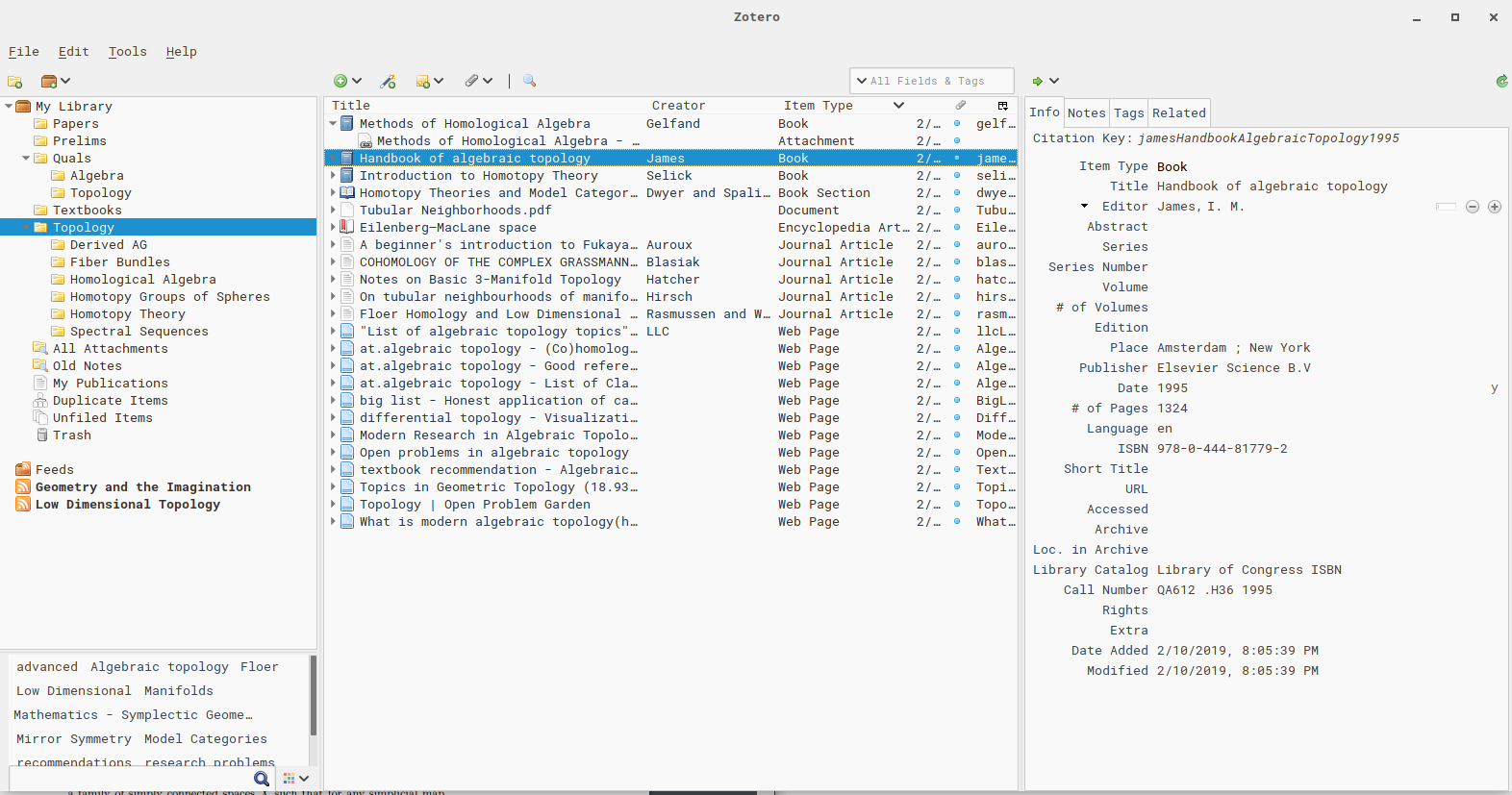

Zotero, on the other hand, I tend to use as an overall organizational tool. I let it import things like papers and lecture notes, and instead link my textbooks into it. This allows Calibre to continue managing books but also lets me attach them to research collections, perform searches, extract annotations, etc.

Zotero is slightly unwieldy, but has a handful of killer features that make it worth the effort:

- Excellent metadata extraction for papers,

- Full-text indexing of all PDFs and annotations

- Maintains a global, automatically updated BibTeX) file using the Better BibTeX plugin, and

- Excellent annotation extraction and report generation using the Zotfile plugin.

Moreover, it has decent internal organizational capabilities using hierarchical “collections”, which allow aliasing items in many separate places that all reference a single, canonical source reference and file.

Zotero does not seem to have any “watch folder” features available, and thus requires either importing via the browser extension manually dragging and dropping files into the Zotero GUI. In both cases, this copies the document into Zotero’s own internal directory structure and can be set to automatically begin populating metadata.

It is easy to separately import links to specific textbooks I am working on. This involves navigating to the proper folder in Calibre, then holding Ctrl-Shift while dragging it into the main collection in the Zotero GUI. This links the file, instead of copying it in and duplicating it. This is critical for annotations, since you always want to be working off of a single file.

Syncing Between Devices

This one is also quite easy, I simply store Calibre’s Library folder and (separately) Zotero’s Library folder on Dropbox. Syncing between PCs is then effortless, although setting Dropbox up on Linux can be tricky as it is controlled through a taskbar/notification icon5

Syncing to Android devices requires something like DropSync to kick off a sync to internal storage or your SD card when files are updated or changed.

Reading and Adding Annotations

I generally want a mix of two types of annotation -– the first freehand drawing, since I occasionally like to color-code things (e.g. to visually distinguish the assumptions of a theorem from the results). The second is being able to either highlight chunks of text or add pop-up notes on the side of the text, both with the intention of being able to digitally search for that text later.

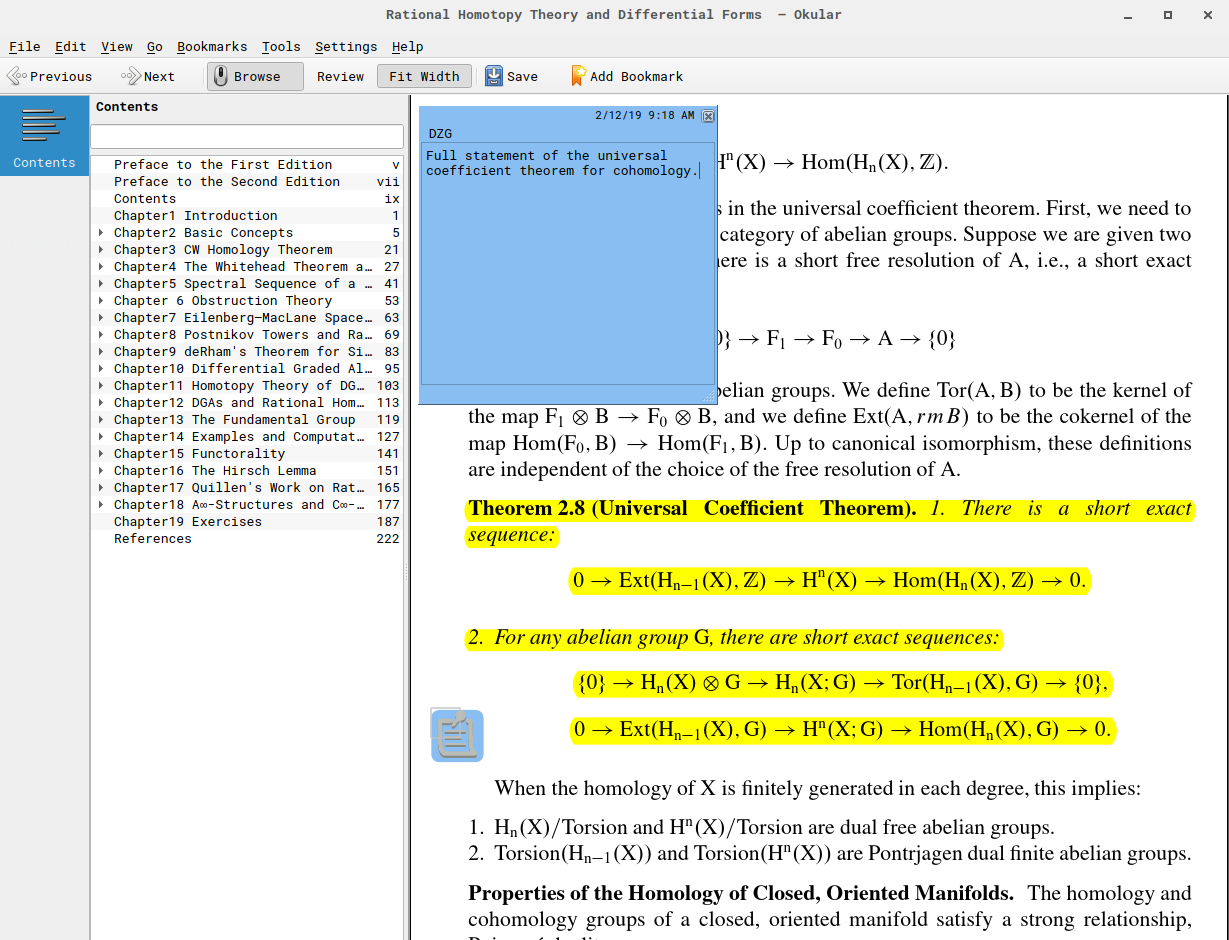

To this end, I’ve settled on two programs that do the job for now: Okular on Linux and Moon+ Reader on Android.

Both have the required annotation capabilities, and additionally, save your view settings position within a document after it is closed. Thus when a document is reopened, it immediately jumps to the last page viewed, which is quite handy. Like most Android applications, Moon+ Reader does not handle stylus inputs gracefully. However, since annotations need to be made in text to be searchable anyway, this doesn’t detract much from its effectiveness.

Another convenience is that (as far as I can tell) the annotations made with these applications are actually attached to the PDF and show up in other viewers, which has not been the case with other viewers I’ve tried.

Annotation Extraction

This is perhaps the crown jewel of this workflow, and at least in my case, makes building and sticking to a slightly convoluted setup absolutely worth it.

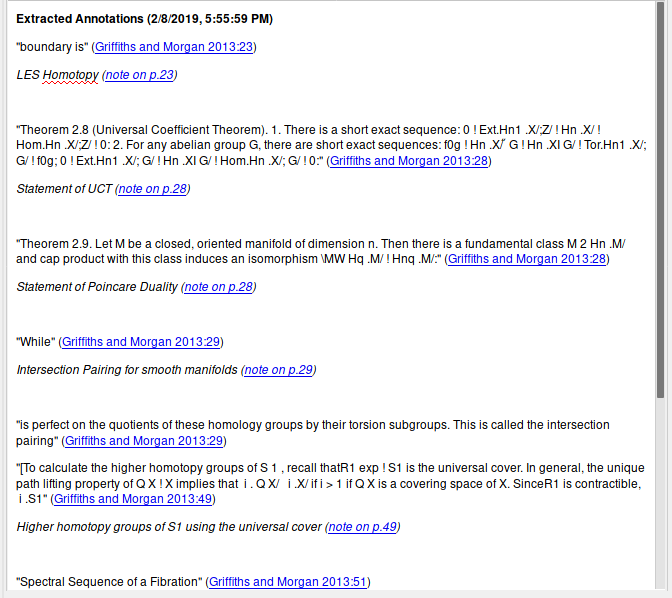

This feature is provided by the combination of Zotero and the Zotfile plugin. Annotations can be extracted from any individual document, creating an HTML page that contains all highlighted text and all notes added via pop-up annotations.

What makes this especially compelling is that it also includes clickable hyperlinks which open the associated PDF jump directly to the page of that annotation!

If desired, you can also select a number of documents and create a joint report, which combines all of the individual reports into a single page. This can be opened in a local browser window, where the hyperlinks will continue to open PDFs directly to the referenced page. You can see an example of what such a report looks like here.6 A full description of how to extract annotations can be found here.

I can not overstate how useful this is -– if you are diligent about annotating and highlighting definitions, theorems, results, or problems within the PDFs you read, you can quickly hit Ctrl-F within Zotero to find a term, which will return the extracted annotation report, which allows you to jump directly into the PDF at the right spot in a matter of seconds.

Subsequently, since your PDFs are OCR’d, you can easily copy-paste text out of it, or use something like the MathPix snipping tool to extract LaTeX for an equation. Since the citation information will already be in your global BibTeX file, it then becomes easy to simply look up the key and cite appropriately.

Conclusion

So that’s all there is to it! It may seem a bit convoluted at first, but for me, it was worth a bit of up-front work to make information easily retrievable. This way, when I really get into a bit of Mathematics and need to find or recall a definition or a proof, I can quickly get to it without getting sidetracked and exhausted from having to hunt it down.

-

Around five months ↩

-

For an overview of this fundamental problem, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homotopy_groups_of_spheres ↩

-

For a slightly more involved treatment, see https://ncatlab.org/nlab/show/homotopy+groups+of+spheres ↩

-

The unstable groups are notoriously difficult to compute; for an overview see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stable_homotopy_theory ↩

-

Some desktop environments (such as Gnome) are phasing out the entire concept of “taskbar icons”, which can be problematic for applications like Dropbox. However, there are generally hacks or workarounds that allow such icons to be displayed again. ↩

-

The PDF links are actually opened through Zotero, which passes off a file name to your default PDF reader. It is thus heavily reliant on the original PDF file’s actual location on the original file system, so the hyperlinks for one person’s reports will almost certainly not work for anyone else without some serious coordination. ↩